Matching the Hatch: Feeding on Top

One of the most exciting ways to fly fish for carp is when you see them feeding on the surface, often called “clooping.” This basically translates to rising carp. For carp, feeding on top can encapsulate everything from aggressively coming up to grasshoppers and beetles, to subtle feeding on midges and algae.

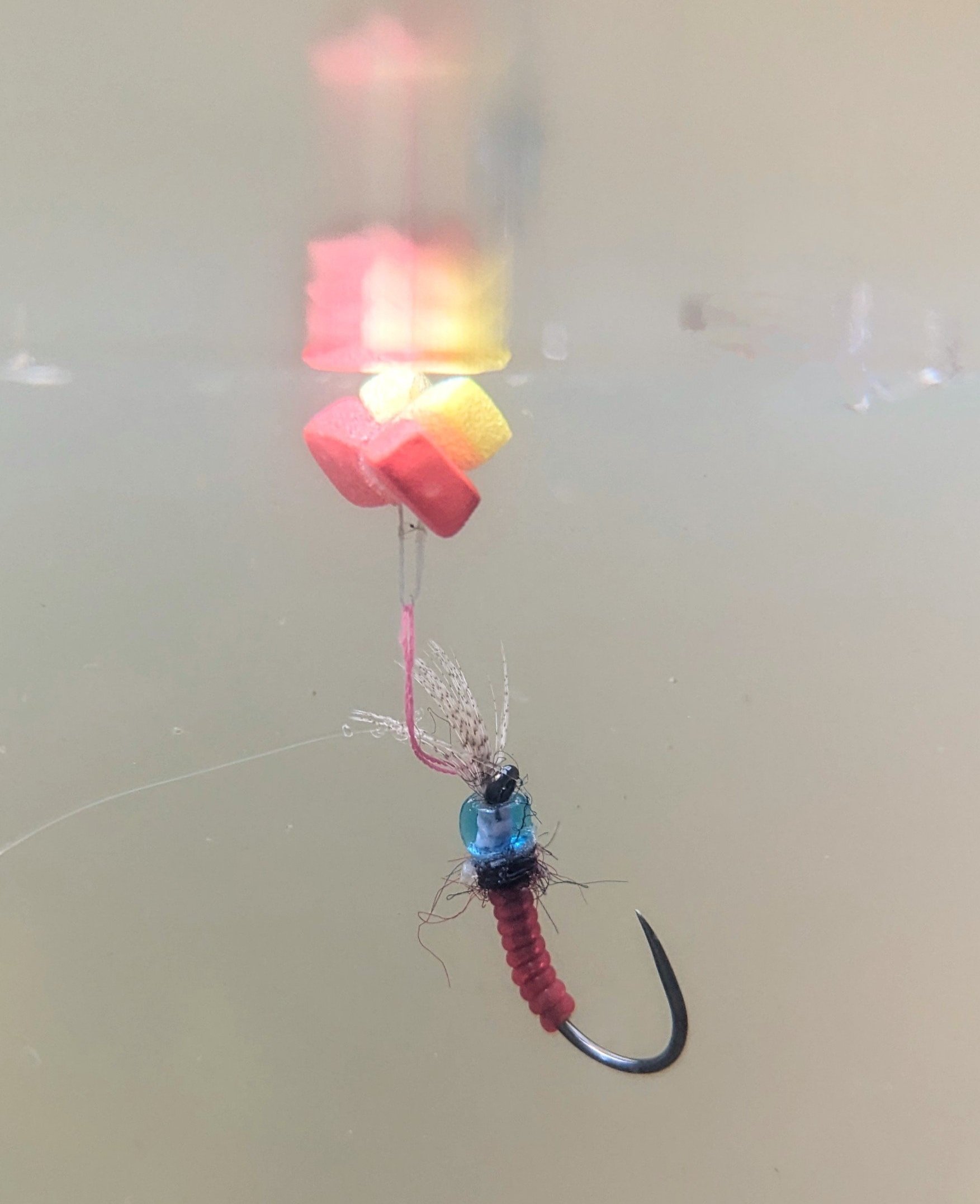

A ballooning spider imitation

As with trout, the ways in which carp come to the surface can tell you a lot about what they are feeding on. When it’s windy, especially coming from the shore, carp will key in on terrestrial insects such as grasshoppers, spiders, and ants. During extreme wind events on cold spring days, I notice larger than average carp porpoising in the waves and eating grasshoppers that were blown out from a large main lake point just up the shoreline. In these events, I’ve landed some of my largest carp by splatting a hopper in the right feeding lane, watching the fish come like dolphins to hit the fly while they ride the waves.

Where I’m at on the Central Coast, we’re lucky enough to have grasshoppers around year-round. But great terrestrial action can be had with ants and spiders as well, especially in areas where the vegetation overlaps with the shoreline, making for easy pickings for the fish when a breeze pushes the insects into the lake. As with most carp flies, you want to make sure these flies are tied on heavy wire hooks that will land heavy fish, while still being light enough to float. My personal favorite hooks for carp are Firehole barbless hooks—their egg hooks and streamer jig hooks are perfect for carp, and barbless hooks are both easier on the fish and hold extremely well.

One thing to remember when using dry flies that sit on top of the surface is that the color doesn't really matter, and the silhouette and size are the main things to focus on. The fish won’t see the color when looking up to the fly, which means you can tie flies with colorful foam, yarn, or wool on top to make the flies easier to spot.

A group of cloopers feeding on algea clumps

As any angler who has fished for trout with dry flies will tell you, you need to wait for the fish to turn on the fly before setting the hook. In general, carp are much larger, so they take a longer time to turn and close their mouths. And depending on what they’re feeding on, carp sometimes keep feeding after taking your fly—especially when feeding on algae—keeping their mouths open for an excruciatingly long few seconds. This means that as an angler you need to watch their mouths closely when fishing dry flies to figure out the timing. Every fish requires slightly different timed hooksets.

During the middle of winter, the fish in one of my local lakes will suspend in big groups right underneath the surface in creek arms, feeding mostly on emerging midges much like trout would. There are usually small microcurrents in these creek arms. The fish will sit in these current lanes and pick clumps of emerging midges out of the surface film. When I first encountered this I started using classic trout-style midge flies in sizes 16-20, but I only managed to successfully land one fish on a size 18 klinkhammer dry fly, by some miracle, as the hook was bent out of shape to the point where I couldn’t use the fly anymore. Every other fish that took the fly either bent out the hook or broke off, as I had to use a light tippet to thread through the smaller hook eyes. The solution was to tie flies with the profile of a size 18 midge on a size 8 or 10 hook, with the whole body just barely behind the eye of the fly. This allows you to actually land the fish you hook with a beefier hook and a heavier tippet.

When carp sit right under the surface film eating on emerging midges, you need that fly to sit just underneath the surface. To match this while seeing the fly and having it on a strong wire hook, I tie a chironomid style nymph, emerging with a foam piece attached to the hook by a sewing thread. The thread allows the nymph to hang freely under the surface film while the foam gives me a visual indication of where the fly is, even with the long casts often needed to catch these surface feeding carp.

Chironomid suspended under a piece of foam

Once it starts to properly warm up in the springtime, most lakes will have an algae bloom of some sort, whether it’s small bits of scum in the surface film or large swaths of thick green stuff. Since carp are able to feed on pretty much anything, you should key in on these events. Keeping your flies simple works best, and one of the top-producing flies in these situations is basically just a clump of EP fibers on a hook in colors matching the algae. This lets the fly sink slightly below the surface film, which can be a deadly tactic when the wind dies down. It lets you drag and drop the fly (in short, casting past the fish and dragging it into their path) without making a wake the way a proper dry fly would. This tactic works well on fish that are feeding on algae in both the surface film and just underneath it. You can usually spot these fish because they’ll be doing just that—cruising slowly underneath the surface to pick off algae clumps, occasionally poking their heads above the surface to eat floating scum.

When there’s a slight breeze, the algae settles in scum/foam lines along the surface. Carp will position themselves in these lanes, feeding on top and sitting like trout in a stream, opening their mouths every now and then to let the wind-created currents bring the food to them. In these situations, a floating algae fly fishes better than the slow sinking one, since the fish often get stuck only feeding on top. My favorite fly in these situations is a foam parachute, with a white piece of foam as the main post and a yellowish hackle wrapped around it. That’s it! It sits right in the surface film, not on top of it and not underneath (like a lot of the algae in the surface film), and the white post is easy to see.

A group of carp sitting in a feeding lane picking off ballooning spiders

These are some common scenarios in which you might encounter carp feeding in or on top of the surface film, although as with every other fish, regional differences can make a lot of difference in the food sources. Make a point to learn the intricacies of each fishery and the different food sources available. In many urban areas, carp have learned to feed on nuts and berries that fall off trees hanging over the water. In other areas you can find fish feeding on mayflies, damselflies, and other regional hatches. The point is—carp not only deserve the same amount of respect when approaching fly choices as trout do, but doing so will also improve your success on the water.